The

Retrial of Joan of Arc, also known as the "nullification trial" or "rehabilitation trial", was a

posthumous retrial of

Joan of Arc authorized by

Pope Callixtus III at the request of Inquisitor-General

Jean Bréhal and Joan's mother

Isabelle Romée. The purpose of the retrial was to investigate whether the trial of condemnation and its verdict had been handled justly and according to ecclesiastical law. Investigations started in 1452, and a formal appeal followed in November 1455. The inquisitor's final summary of the case in June 1456 described Joan as a

martyr and implicated the late

Pierre Cauchon with heresy for having convicted an innocent woman in pursuit of a

secular vendetta. The court declared her innocent on 7 July 1456.

Background[edit]

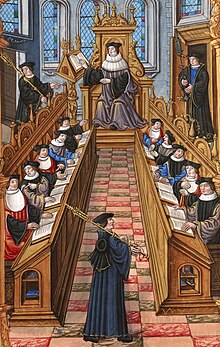

Theologians from the University of Paris were involved in the trial of Joan of Arc in 1431.

Following Joan of Arc’s death in 1431,

Charles VII was said to have "felt a very bitter grief" when he heard the news, "promising to exact a terrible vengeance upon the English and women of England".

[1] However, for many years his government failed to make much headway on the battlefield, and the English held on to most of their conquests in northern France.

[2]

Prior to 1449, a number of factors stood in the way of any possible review of Joan’s condemnation. Firstly, the English were still in possession of Paris. The

University of Paris had provided assessors for the trial of condemnation at

Rouen.

[3] In May 1430, Paris had been held by the Anglo-Burgundian alliance, and the theologians and masters of the university had written to Duke

Philip the Good of

Burgundy asking that Joan be transferred to the English so she could be placed on trial.

[4] Since the university had played an active part in the proceedings, they could only be brought to account once Paris was captured on 13 April 1436.

[5]

Secondly, Rouen – the site of the trial – was also still held by the English. The documents relating to the original trial were kept in Rouen, and the town did not fall into Charles VII's hands until November 1449.

[6] Historian

Régine Pernoudmakes the point that "So long as the English were masters of Rouen, the mere fact that they held the papers in the case, a case which they had managed themselves, maintained their version of what the trial had been".

[6] She adds: "to reproach the King or the Church with having done nothing until that time is tantamount to reproaching the French government with having done nothing to bring the

Oradour war criminals to justice before 1945".

[6]

Initial attempts[edit]

Bouillé's review of 1450[edit]

On 15 February 1450, Charles ordered the clergyman Guillaume Bouillé, theologian of the University of Paris, to inquire into the ‘faults and abuses’ committed by Joan's judges and assessors at Rouen, whom Charles accused of having "brought about her death iniquitously and against right reason, very cruelly".

[6] This could potentially cause some difficulties, as a member of the University of Paris was being asked to investigate the verdict based on advice given by other members of the same university, some of whom were still alive and holding prominent positions within Church and State. Charles therefore was very cautious, limiting Bouillé's brief to a preliminary investigation in order to ascertain ‘the truth about the said process and in what manner it was conducted.’

[7] Although there was a suspicion of an unjust condemnation, there was no suggestion at this stage of an inquiry leading to the Inquisition revoking its own sentence.

[8]

Yet there were too many prominent people who had been willing collaborators in 1430 that had changed their allegiance once Charles had regained Paris and Rouen that had too much to lose for the proceedings against Joan to be reopened.

[9] They included men such as

Jean de Mailly, now the

Bishop of Noyon, who had converted to Charles' cause in 1443, but in 1431 had signed letters in the name of King

Henry VI of England, guaranteeing English protection to all those who had participated in the case against Joan.

[10] An even greater obstacle was

Raoul Roussel,

archbishop of Rouen, who had been a fervent supporter of the English cause in

Normandy and had participated in Joan’s trial, until he too took an oath of loyalty to Charles in 1450.

[11]